Latest notable terms from this and last week’s Slate Culture Gabfest (feel free to email me suggestions or leave them in the comments to the main page). [continue reading…]

Latest notable terms from this and last week’s Slate Culture Gabfest (feel free to email me suggestions or leave them in the comments to the main page). [continue reading…]

[From my Webnote series]

Gene Callahan, in Private Domains and Immigration, in 2003, concluded, in a critique of Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s views on immigration:

giving more power to the state, based on an arbitrary set of ideals as to who should be allowed to come to the US (or any other country), ideals that are divorced from any actual entrepreneurial judgment, is not the answer to these problems. True freedom is the only answer.

Callahan, in 2010, in The Nature of Ideology, drawing inspiration from cow-psychologist Temple Grandin and his “second stay in Switzerland,” now writes:

Spending more time there on trip two, I thought I was in the most naturally orderly and civic-minded place I had ever been – and, I realized, if the Swiss ever adopted the open border policy I had advocated until then, that place would be gone in a decade. Now, when I recently expressed some reservations about unrestricted immigration on a libertarian blog, I was immediately accused of being a ‘xenophobe.’

Interestingly, these latter observations are similar to those of Ralph Raico and Hoppe. Raico argued:

Free immigration would appear to be in a different category from other policy decisions, in that its consequences permanently and radically alter the very composition of the democratic political body that makes those decisions. In fact, the liberal order, where and to the degree that it exists, is the product of a highly complex cultural development. One wonders, for instance, what would become of the liberal society of Switzerland under a regime of “open borders.”

In other words, the argument is that relatively liberal societies would certainly soon become less libertarian if they opened their borders.

And Hoppe argues here 1 (emphasis added):

It is not difficult to predict the consequences of an open border policy in the present world. If Switzerland, Austria, Germany or Italy, for instance, freely admitted everyone who made it to their borders and demanded entry, these countries would quickly be overrun by millions of third-world immigrants from Albania, Bangladesh, India, and Nigeria, for example. As the more perceptive open-border advocates realize, the domestic state-welfare programs and provisions would collapse as a consequence. This would not be a reason for concern, for surely, in order to regain effective protection of person and property the welfare state must be abolished. But then there is the great leap—or the gaping hole—in the open border argument: out of the ruins of the democratic welfare states, we are led to believe, a new natural order will somehow emerge.

The first error in this line of reasoning can be readily identified. Once the welfare states have collapsed under their own weight, the masses of immigrants who have brought this about are still there. They have not been miraculously transformed into Swiss, Austrians, Bavarians or Lombards, but remain what they are: Zulus, Hindus, Ibos, Albanians, or Bangladeshis. Assimilation can work when the number of immigrants is small. It is entirely impossible, however, if immigration occurs on a mass scale. In that case, immigrants will simply transport their own ethno-culture onto the new territory. Accordingly, when the welfare state has imploded there will be a multitude of “little” (or not so little) Calcuttas, Daccas, Lagoses, and Tiranas strewn all over Switzerland, Austria, and Italy. It betrays a breathtaking sociological naiveté to believe that a natural order will emerge out of this admixture. Based on all historical experience with such forms of multiculturalism, it can safely be predicted that in fact the result will be civil war. There will be widespread plundering and squatterism leading to massive capital consumption, and civilization as we know it will disappear from Switzerland, Austria and Italy. Furthermore, the host population will quickly be outbred and, ultimately, physically displaced by their “guests.” There will still be Alps in Switzerland and Austria, but no Swiss or Austrians.

As for Callahan getting smeared as a “xenophobe” for having reservations about unrestricted immigration, this is common–from criticisms such as he himself leveled at Hoppe, and so on (followup). Make of this what you will.

(To be clear, I’m pro-immigration and opposed to state restrictions on immigration.)

Update: See some recent tweets:

It’s hard for an ancap to support the INS, or any other federal goonds. OTOH it’s hard to support mass subsidized immigration either. Hoppe himself sees the heart of the problem is one caused by state democracy, welfare, and intervention: if the state prevents a citizen from inviting some outsiders, that violates his rights; it is what Hoppe calls forced exclusion. He specifically criticizes state immigration policy when it violates the rights of its citizens to invite whoever they want to their property. OTOH if the state subsidizes mass immigration and forces people to support and associate with and employ and give voting rights to these outsiders by means of antidiscrimination laws, welfare, and public roads and transportation and other state owned public property and facilities, this violates the rights of citizens by way of forced integration. Both forced exclusion and forced integration violate property rights of the citizens, according to Hoppe. Hoppe’s solution–the “first best”–is to abolish the state so that neither forced exclusion nor forced integration occur. Barring that, his “second best” solution as to a reasonable way to minimize both, to reduce the rights violations from either forced exclusion or forced integration, is to deny outsiders the use of public resources owned by citizens (because given welfare and other legal rights, they will have access to this as soon as they are permitted access) unless they are invited by a citizen who takes responsibility for them. By prohibiting them from accessing public resources (without an invitation) you reduce forced integration and related costs and rights violations; by permitting someone who is invited by a citizen, you reduce the forced exclusion problem (and by making the invitee-citizen responsible, you further reduce the forced integration problem since presumably there is a lower chance the immigrant will be a criminal or on the dole, since a citizen has to vouch for and to some degree even be responsible him). Until we abolish the welfare state, voting, and the state itself, you can see why his solution has an appeal to some libertarians: it’s an attempt to reduce both types of rights violations perpetrated by the state: forced exclusion, and forced integration/mass-subsidized immigration. See relevant quotes here stephankinsella.com/2007/09/boudre n.b.

Interesting discussion about the libertarian position on immigration/open borders between my brothers El-Bobborino

and

. Dave does a good job giving his take on the Hoppean-type view on this matter, on second-bests, and the like. I tried before to explain, myself, what this Hoppean position really is: see twitter.com/NSKinsella/sta and my article “A Simple Libertarian Argument Against Unrestricted Immigration and Open Borders” stephankinsella.com/2005/09/a-simp. In the Smith-Murphy discussion, go to around 37 minutes here, where they talk about Gramercy Park in NYC. This is a good hypo Dave gives but let me refine it a bit youtu.be/1EZ6-Pn9j88?si So imagine there is a private neighborhood that owns a park in NYC, Gramercy Park, and only the residents and owners have keys to use the park. So therefore it’s very nice since no outsiders, bums, vagrants can use it. Let’s say these residents all pay their HOA (I know, I know, unemployed libertine libertards hate HOAs, but let it pass) a fee to hire private security guards to make sure no outsiders or bums use the park. Now one day the state expropriates Gramercy Park so is now it’s official owner, and they tell the previous owners they have to pay a tax to the state and the state will provide its own police, but everything will continue as before. Of course, it will be more expensive and less efficient, but the residents grumble and move on. They still have their little park, and instead of paying HOA fees to pay for private security, they are now paying a special tax and the state is providing the security personnel. So they are worse off because they are paying more and getting worse services, but only so much damage has been done to them. But now comes along an open-borders libertard type who thinks state-owned property ought to be treated “as if” it is unowned. In other cases, like borders, or state schools, they say well the state has no right to stop an immigrant from coming in; he’s not committing aggression. The state has no right to stop a crackhead from walking into a public elementary school classroom; after all he’s not committing aggression, and the property is “unowned.” So by this logic, they would have to say that the government, as owner of Gramercy Park, has no right to stop bums from decamping there. So let’s say the government takes the advice of our helpful local libertarian and tells its cops “stop banning bums from using the park”. So now the local residents find their beautiful park ruined and unusable. Can you not see how this state change in its policy about who can use public property that it has seized, adds insult to injury? Actually it adds injury to injury. If the state commandeers my private park and makes me pay taxes for it and runs is less efficiently, I am harmed to a certain degree but I still have the use of my park. If the state then starts allowing all-comers in, then it harms me more. See? n.b.

Interesting admission by left-libertarian

in 2005: “Hoppe’s views on immigration are based on an interpretation/application of libertarian rights theory that I strongly disagree with, but I don’t think it’s self-evidently un-libertarian. Given the current system of all-pervasive state property, both an open-borders policy and a closed-borders policy are going to violate some libertarian rights. So it comes down to a question of which policy is worse. “I think closed borders are worse, Hoppe thinks open borders are worse; we both agree that ultimately there should be no state borders at all and that individual property owners should have soveriegnty over their own property, so it’s just a disagreement about the second-best solution. “Anyway, given that Mises advocated conscription, 100% libertarian purity can hardly be the standard to determine who counts as a champion of liberty.” stephankinsella.com/2005/04/the-or This echoes my view that Hoppe recognizes that given the modern welfare democratic state, any immigration “policy” will violate rights. So Hans favors reducing the overall amount of rights violations. The best way to do this is to have no state at all and 100% private property. But barring that: have a sponsor system, which would reduce both types of rights violations. Increase legal immigration in the US via a sponsorship system, which would increase overall immigration and also overall quality immigration, and would reduce forced integration costs, and also reduced forced exclusion. Seems like a win win to me. n.b.

https://twitter.com/NSKinsella/status/1759447284360614347:

It’s hard for an ancap to support the INS, or any other federal goonds. OTOH it’s hard to support mass subsidized immigration either. Hoppe himself sees the heart of the problem is one caused by state democracy, welfare, and intervention: if the state prevents a citizen from inviting some outsiders, that violates his rights; it is what Hoppe calls forced exclusion. He specifically criticizes state immigration policy when it violates the rights of its citizens to invite whoever they want to their property. OTOH if the state subsidizes mass immigration and forces people to support and associate with and employ and give voting rights to these outsiders by means of antidiscrimination laws, welfare, and public roads and transportation and other state owned public property and facilities, this violates the rights of citizens by way of forced integration. Both forced exclusion and forced integration violate property rights of the citizens, according to Hoppe. Hoppe’s solution–the “first best”–is to abolish the state so that neither forced exclusion nor forced integration occur. Barring that, his “second best” solution as to a reasonable way to minimize both, to reduce the rights violations from either forced exclusion or forced integration, is to deny outsiders the use of public resources owned by citizens (because given welfare and other legal rights, they will have access to this as soon as they are permitted access) unless they are invited by a citizen who takes responsibility for them. By prohibiting them from accessing public resources (without an invitation) you reduce forced integration and related costs and rights violations; by permitting someone who is invited by a citizen, you reduce the forced exclusion problem (and by making the invitee-citizen responsible, you further reduce the forced integration problem since presumably there is a lower chance the immigrant will be a criminal or on the dole, since a citizen has to vouch for and to some degree even be responsible him). Until we abolish the welfare state, voting, and the state itself, you can see why his solution has an appeal to some libertarians: it’s an attempt to reduce both types of rights violations perpetrated by the state: forced exclusion, and forced integration/mass-subsidized immigration. See relevant quotes here stephankinsella.com/2007/09/boudre n.b.

- Natural Order, the State, and the Immigration Problem (Vol. 16 Num. 1, Winter 2002): 75-97, in The Great Fiction). [↩]

China is widely viewed as a “threat” to the US because of its perceived rapid and unstoppable economic growth. This is, in my view, doubly confused. First: if the premise were true, this would be good, not bad. Second: I don’t think China is in such great shape. Unfortunately.

China is widely viewed as a “threat” to the US because of its perceived rapid and unstoppable economic growth. This is, in my view, doubly confused. First: if the premise were true, this would be good, not bad. Second: I don’t think China is in such great shape. Unfortunately.

Some free market economists think otherwise. Peter Schiff “predicts that China will overtake the U.S in terms of Gross Domestic Product before 2020.” Jim Rogers thinks “China will likely constitute tomorrow’s most powerful nation-state.”

I’ve been working for years now for a company with factories and extensive dealings in Taiwan and China. It’s been my opinion for some time that China is a primitive basket case. Land is leased, not owned. The communist party corruption is everywhere. The Asian mentality is far different than the western one; they are less innovative, more subservient and servile, more order-following, more collectivist and less individualistic. Poverty and peasantry are rampant. Asians are far more racist and superstitious than Americans (everyone is more racist than Americans in my experience). You have to get permission for everything. There are currency controls. Contracts are not respected–they are signed because they are viewed as red tape and then they start being renegotiated the next day. And on and on.

In my view, America is, for all our faults, still, by far, the strongest and best large economy in the world. Who can match the US? Canada is too small. Japan is not quite our size and has its own problems. Europe is like an older, more kleptocratic version of the US–and is probably second best in the world. South America is a basket case of banana republics. Africa is even worse. Russia and Central Europe?–mired in pessimism and corruption and the tendrils of the wreckage of communism. Of the rest, I think India has a better chance than China, for two reasons: they speak English, and they inherited the English property rights system–unlike in China where you still have to lease land from the state for 50 years instead of buying it. And I think India is a basket case too, unlikely to improve much for many decades. So the US is and will remain preeminent, in my view–despite all our problems. (See also Jonathan Bean’s America’s Hidden Strength: Babies, Immigration.) Unfortunately, this will allow our parasitical state to maintain its warfare-welfare state (see my post Hoppe on Liberal Economies and War).

An American friend of mine living in China sent me some of his thoughts, which I provide, with editing, and anonymously, below:

China is [screwed], I tell you. This place is one big pile of poo. Jim Rogers and Peter Schiff are wrong, at least about China. Jim Chanos is right! [See also Jim Rogers: China not in a bubble, Chanos couldn’t spell China; China May ‘Crash’ in Next 9 to 12 Months, Faber Says. Also note: Mark DeWeaver, who has written for the Mises Institute before, recently gave a speech about Chinese monetary policy. There’s some interesting meat in both the audio and corresponding slides.] [continue reading…]

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (17.0MB)

Subscribe: RSS

I was on The Peter Mac Show on May 12, 2010, with my fellow Libertarian Standard co-blogger Rob Wicks. We discussed a variety of matters, including whether libertarians should use the word “capitalism,” also anarchy, IP and other topics. The MP3 file is here.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (6.8MB)

Subscribe: RSS

My reply to one “Chris George’s” post No, The Non-Aggression Principle is Not Enough (see Reply to Left-Libertarians on “Capitalism” for other discussions with Chris):

Chris, you are getting better. Glad you accept the NAP as a basic rule of thumb. But confusions remain.

“If we got down to the really nitty gritty, I’m sure you could find plenty of people who would deny my libertarianism at all since I’m a rationalist, anarchist, localist, pluralist, and moral subjectivist before I’m a libertarian”

As long as you are opposed to aggression we don’t “deny your libertarianism.” We welcome your opposition to aggression. THe word “before” is confusing; you don’t mean chronologically, and you won’t give an example of where you value something more than non-aggression such that you would condone aggression. (BTW this is exactly what conservatives say: “Hey, we are as against aggression as the next guy, but unlike you libertarians it’s just one of MANY “values” we hold. So we have to balance them.” So they leave the door open for moral majority laws etc. This is what you are doing too, in principle–you need to work to root that out. we must oppose aggression *on principle*. Your *reasons* can be your own. But it has to be a principled opposition, not a mere tentative rule of thumb).

You also write: “While I don’t accept the NAP absolutely do to issues of property and efficacy, it’s something that I think should be looked to first in the majority of cases.”

you mean “due” to. But still, you seem to want to leave the door open to condone aggression against private property due to some kind of leftist sentimental abhorrence of property rights. But all human rights are property rights, of course. You cannot be against agression and a libertarian without objecting to trespass against private property rights, of course.

” If we can define a decent standard of property/possession/whatever-you-want-to-call it,”

we have already done this. Next!

““no, the NAP is not enough.” Let me explain and it doesn’t lead to specifically “left” answers.

For the most part, the reason is strategic. Simply put, most people don’t want to hear some philosophical gibberish about “aggression” or “how ethics ‘derived’ from the nature of man are the ‘correct’ ethics.””

As for your first “reason,” I stopped reading there. You are conflating truth with strategy and persuasiveness, a common mistake of the activist mindset (see my The Trouble with Libertarian Activism, http://www.lewrockwell.com/kinsella/kinsella19.ht… .) You cannot say the NAP is wrong because it doesn’t persuade many people. this makes no sense at all.

Then you get to your “second” reason which is equally confused:

“The second reason the NAP is not enough is just simply due to its relative worthlessness in real life. Would you really want to live in a world where the only constant is non-aggression? A world where everyone was a shallow, selfish dickhead who avoided aggression would suck.”

This again makes no sense. Libertarianism is a narrow philosophy concerned with interpersonal violence. But we are not just libertarians. As humans we can and should oppose meanness and shallowness, etc. Living in a good society means (a) being free from aggression; and (b) a lot of other things, like culture, art, benevolence, civilization, civility, charity, and so on.

Recognizing this in no way argues against the non-aggression principle! Just because living a crime-free life is “not enough” does not mean we should not oppose crime on principle!

Think straight, man. You have potential, but you have got to get out of this muzzy, confused, left-emotional way of thinking. Think clearly and all this is easy to sort out.

It is clear that the left-libertarians have lost in their campaign to demonize the word “capitalism.” Nice try, fellas, but you lost. Libertarians are not buying your strained arguments and pointless attempt to fight semantic battles. Capitalism as a word just means private ownership of the means of production. I point you to a dictionary. This is obviously compatible with libertarianism, and arguably an essential part of the economy of an advanced libertarian society. Crony capitalism and corporatism are unlibertarian, but laissez-faire capitalism is not. The origin of the term may be interesting but does not change what meaning it has now. There is nothing wrong with using capitalism to describe a key aspect of a libertarian social order, as long as one is clear to distinguish it from crony-capitalism. See: Capitalism, Socialism, and Libertarianism; Rothbard: “True anarchism will be capitalism, and true capitalism will be anarchism”; Reply to Left-Libertarians on “Capitalism”; Left-Libertarians Admit Opposition to “Capitalism” is Substantive.

And it is not we libertarians who have things to learn from the left: rather the opposite is true. We non-prefix libertarians are not left, but we are also not right, and it’s wrong of left-libertarians to accuse us of being “right” merely because we reject the equally confused and false doctrines of the left. We already know that crony capitalism is wrong. Furthermore, we are aware of the fact that state intervention has distorted the market. We also do not just rubber stamp and endorse current land holdings out of some fetish for the status quo; non-prefix libertarians believe that if someone can show a better claim to a given piece of property than the current legal owner, he should prevail. But unless and until this occurs, the current legal owner, so long as he is private, has a better claim to the property than anyone else and should be its owner (property held by the state should be taken from it, of course).

Go capitalism, go! Here is some recommended recent pro-capitalist libertarian reading:

- Peter Klein’s new book The Capitalist and the Entrepreneur: Essays on Organizations and Markets

- Thank Goodness for Capitalism, by Jonathan M. Finegold Catalan, Mises Daily (Tuesday, May 11, 2010)

- Crony Capitalism Is NOT Capitalism, Dominick T. Armentano, Independent.org (May 10, 2010)

I was a guest on the May 9, 2010 episode of BlogTalkRadio’s show Anarchy Time, hosted by James Cox. Other guests included C4SS Development Specialist Mariana Evica, Wilt Alston, and Stefan Molyneux. (Local MP3.)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (27.7MB)

Subscribe: RSS

TokyoTom, enviro-global-warming anti-corporation libertarian, in Risk-shifting, BP and those nasty enviros, has some criticisms of Lew Rockwell’s Feel Sorry for BP?

1. “It should be obvious that BP is by far the leading victim, but I’ve yet to see a single expression of sadness for the company and its losses.”

BP is the leading “victim”? Victim of what/who? Sure, they’re a target (1) for all manner of evil people whose livelihoods or enjoyment of their property or common property are directly or indirectly affected by the spill, (2) for evil enviro groups (relatively well-off citizens who profess to care about how well/poorly government manages the use of “common resources” by resource extraction industries), and (3) for evil governments and politicians looking to enhance their own authority/careers. But these are all a consequence of the accident, and not a cause of it. Has BP been defrauded, tricked or strong-armed into drilling anywhere? Is BP the “victim” of its own choices?

Even if one concedes that some criticisms of BP will be unfair, how can BP possibly be cast as the LEADING victim – as opposed to all of the others whose livelihoods or property are drastically affected by this incident, which they had no control over whatsoever?

BP is a victim in the sense that a terrible tragedy just happened to it, and it’s gonna cost it dearly. It’s the leading victim assuming the others damaged are going to be compensated from BP. The point is it’s a bad thing that’s happened to it.Why not feel sorry for them?

2. “The incident is a tragedy for BP and all the subcontractors involved. It will probably wreck the company”

The incident will certainly be costly for the firms involved, but the firms will survive the death of employees, and there is certainly very little risk indeed that BP will be “wrecked” by the spill. Far from it; it is unlikely that BP will even bear the principal costs of cleanup efforts, much less the economic damages to third parties that federal law apparently caps at $75 million.

Have you not heard of “INSURANCE”? A little thinking (and Googling) would tell you that BP (and its subcontractors) has plenty of it. To the extent BP is NOT insured, it has ample capability to self-insure, unlike all of the fishermen, oystermen and those in the tourist industry who are feeling significant impacts. Insurers will bear the primary burdemn, not BP.

Obama has threatened BP and they have caved in, agreeing to pay above the $75M cap. And the cap was in exchange for a tax on oil companies to be put into the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund for such emergencies–do you think that BP will be able to get that tax refunded? Naah.

3. “we might ask who is happy about the disaster: 1. the environmentalists, with their fear mongering and hatred of modern life”

Sorry, but this is perverse: enviros might feel that they have been proven right – and you might be annoyed that they can make such a claim – but they certainly aren’t “happy” with any of the loss of life, damage to property or livelihoods of the little guy (or of bigger property owners), or to a more pristine marine environment that they value.

Aren’t happy? Have you seen, say, Spill Baby Spill, Boycott BP! ? And another tolerant, caring liberal on Slate’s Political Gabfest Facebook page said, “I don’t get the calls for pity. Boohoo another oil giant might have bankrupted itself.” These misanthropic sickos oppose nuclear power, which makes fossil fuels necessary. They act like they hate BP. Why? For making a mistake? Mistakes are inevitable. For drilling for oil? Why? We need oil.

Your projection of happiness at damages to common resources/private property and hatred of modern life is especially perverse, given your own explicit recognition that government ownership/mismanagement of commons, and setting of limits on liability both skew the incentives BP faces to avoid damage, and limit the ability of others (resource users and evil enviros) to directly protect or negotiate their own interests. Why is the negative role played by government any reason to bash others who use or care about the “commons”?

No libertarian is in favor of liability caps. What is he talking about?

We have seen Austrians – sympathetic to the costs to real people in the rest of the economy – rightly call for an end to a fiat currency, central banking and to moral-hazard-enabling deposit insurance and oversight of banks. In an April 9 post by Kevin Dowd on the financial crisis, we even had a call “to remove limited liability: we should abolish the limited-liability statutes and give the bankers the strongest possible incentives to look after our money properly” – but Dowd’s comments simply echoed in the Sounds of Silence. Why do you and others refuse to look at the risk-shifting and moral hazard that is implicit in the very grant of a limited liability corporate charter – not only in banking, but in oil exploration and other parts of the economy?

Removing artificial caps on liability has nothing to do with the limited liability of passive shareholders in a corporation. Their liability is limited simply because they are not causally responsible for the torts of employees of the company in which they hold shares.

6. Finally, like BP, you have understated the degree of the oil leakage; BP initially estimated 1000 bpd, but later agreed with estimates by others that the leak is at least about 25,000 bpd, with risks of an even larger blowout.

So what? It is what it is.

Good enough for Rothbard, good enough for me.

The movement that I’m in favor of is a movement of libertarians who do not substitute whim for reason. Now some of them do, obviously, and I’m against that. I’m in favor of reason over whim. As far as I’m concerned, and I think the rest of the movement, too, we are anarcho-capitalists. In other words, we believe that capitalism is the fullest expression of anarchism, and anarchism is the fullest expression of capitalism. Not only are they compatible, but you can’t really have one without the other. True anarchism will be capitalism, and true capitalism will be anarchism.

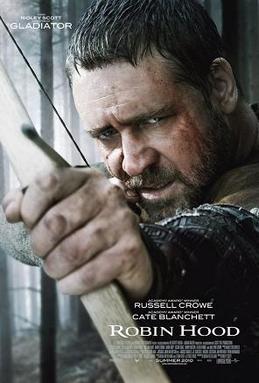

I, for one, am sick of the Robin Hood myth and movies. Or I thought I was. On the latest episode of Mark Kermode’s BBC film review podcast, there’s a fascinating discussion with Russell Crowe and “Billy Bragg” about the upcoming Ridley Scott film Robin Hood, starring (and co-produced by) Crowe. The new movie is a departure from other versions, with Robin Hood involved in the Magna Carta and also the Forest Charter which, “In contrast to Magna Carta, it provided some real rights, privileges and protections for the common man against the abuses of the encroaching aristocracy.” One line I like from the Forest Charter: “Any archbishop, bishop, earl, or baron who crosses our forest may take one or two beasts by view of the forester, if he is present; if not, let a horn be blown so that this [hunting] may not appear to be carried on furtively.”

I, for one, am sick of the Robin Hood myth and movies. Or I thought I was. On the latest episode of Mark Kermode’s BBC film review podcast, there’s a fascinating discussion with Russell Crowe and “Billy Bragg” about the upcoming Ridley Scott film Robin Hood, starring (and co-produced by) Crowe. The new movie is a departure from other versions, with Robin Hood involved in the Magna Carta and also the Forest Charter which, “In contrast to Magna Carta, it provided some real rights, privileges and protections for the common man against the abuses of the encroaching aristocracy.” One line I like from the Forest Charter: “Any archbishop, bishop, earl, or baron who crosses our forest may take one or two beasts by view of the forester, if he is present; if not, let a horn be blown so that this [hunting] may not appear to be carried on furtively.”

The discussion about this with Crowe and Bragg (9:00 to about 32:10 of the podcast) goes into how the Norman aristocracy unjustly invaded the land rights of the common people, which was redressed to some degree by the Forest Charter. Sounds interesting.

Update: see Rand on the Injuns and Property Rights:

See Hoppe, “Of Common, Public, and Private Property and the Rationale for Total Privatization,” as ch. 5 of The Great Fiction, Part II, discussing the right of groups to homestead partial easements of land by use. I have written a bit on some similar matters, about how the English “enclosure” did violate some pre-existing easement rights, so in some sense “property” is “theft” as Proudhon said (meaning property rights decreed legislatively by the state that trampled on pre-existing easement rights).

Creative Common Law Project, R.I.P. and Waystation Libertarians:

From Jamin Hübner, before he became a socialist:

Another myth is more fundamental: that of “free and voluntary exchange” that underlies all market interactions. This individualistic, utilitarian, and neoliberal dogma, repeated ad nauseum by anarcho-capitalist and neoconservative apologists, was perceptively challenged by William Thompson nearly two centuries ago when he observed that people without capital (e.g., tools and materials to produce)—like former serfs who were evicted from the manor during the enclosure movement—have no choice but to sell themselves. “The selling of their labor power was not a free exchange, but was coerced. The threat of starvation was as coercive as a threat by violent means” (E. K. Hunt and Mark Lautzenheiser, A History of Economic Thought, 158).

Gene Epstein and I were discussing this the other day and I observed that it could be argued that this violates the easement rights of the ranchers/hunters, like the enclosure laws that left-libertarians have opposed (“property is theft”). I pointed out that even in Hoppe’s theory you can have group easement rights that are violated by enclosure/fencing. Here is the email I sent him:

Re our brief discussion—Hoppe on group easements: “Of Private, Common, and Public Property and the Rationale for Total Privatization” — see in particular Part II.

Re the Forest charter, enclosures, and so on — Robin Hood, Magna Carta, and the Forest Charter. And how the enclosure movement could be seen as a type of theft of preexisting easements–a la Hoppe’s comments too.

[TLS]

I was trying to figure out the relative wattages of various Apple power adapters I have–for the MacBook, MacBook Air, and MacBook Pro–to see which is compatible with other MacBooks. While doing this it occurred to me that it might be helpful to provide a quick little factoid/tutorial for non-EEs who get confused by the concepts of voltage, current, and power.

I was trying to figure out the relative wattages of various Apple power adapters I have–for the MacBook, MacBook Air, and MacBook Pro–to see which is compatible with other MacBooks. While doing this it occurred to me that it might be helpful to provide a quick little factoid/tutorial for non-EEs who get confused by the concepts of voltage, current, and power.

The electrons flowing through a conductor (wire) are a current, represented by i or I, and measured in amperes, or amps. It’s analogous to water flowing through a hose. (Note: the imaginary number i is thus referred to as j by EEs to distinguish it from current, i.) The voltage, v or V, represents the amount of “pressure” pushing the current through the conductor. These concepts are often confused by laymen, used interchangeably, etc. For example, you can be killed if a large enough current passes through your body–amps. Your body has a certain resistance R, measured in ohms, ? (or impedance, if you take into account complex (imaginary, frequency) aspects; incidentally, the analogous concept for magnetic flux is called reluctance–I’ve always loved those three terms: resistance, impedance, and reluctance; if we need another, I suppose stubbornness might do). The bigger the resistance, the more pressure or voltage V is needed to push through a given current I. There is a simple relation: V=IR, or I = V/R. For example, if you have 10V and a 10 ? resistor, there is 1A of current. If you get electrocuted, it’s the current passing through you–the amps–that kills you.

Anyway, electrical power is measured in terms of Watts, and power, P, is determined by a simple equation: P=VI. That is, it’s directly proportional to the voltage and the current. When you see a power adapter that is rated to provide, say, 18.5V at 4.6A, as with Apple’s 85W MagSafe Power Adapter, you’ll notice that you get the 85W figure by multiplying the voltage times the current: 18.5 x 4.6 = 85.1. The point is, this is a very handy relationship to know, and it’s easy to remember: P=VI. If you know the V and I, you can figure out the wattage (power). In addition, because of the V=IR relationship, you can figure out, say, current, if you know resistance and power. Or say you have a 100? lightbulb, and it’s powered by a 110V outlet. If you want to figure out the current, it’s I=V/R = 110/100 or about 1 amp. This helps to explain why some yards use “low voltage” lighting: if there is low voltage, it’s hard for a human (say) to get shocked badly. If you touch the terminals of a 1.5V battery, the resistance of your body combined with this voltage means the current is very small. To have a decent light from low voltage, you need much lower resistance bulbs, so that you get the wattage (light) output that you want. Likewise, although homes use 110V power, this is stepped down from the higher-voltage power lines. The voltage on power lines is very high so that there is less current for a given power. P = VI, so for the same power P, if you increase V, you can decrease I. The reason you want to do this is the more current, the more heat is generated and energy wasted.

Update: See Bitcoin Freedom Fund.

From The Libertarian Standard. Older related posts follow:

Besides traditional activism such as politics and writing and speaking, on occasion intellectual entrepreneurs try to find more innovative and creative ways to work for a free society. Examples include various forms of “new libertarian nation” projects (like Patri Friedman’s Seasteading Institute, and the Free State Project), as well as the idea of subscription-based patrol and restitution advanced by Guillory and Tinsley, or Stephen Fairfax’s ingenious proposal presented at Austrian Scholars Conference 2010, “Returning Gold to the Consumer Marketplace” (discussed here).

Along these lines, I’ve been fascinated with an idea I got when I read about an utterly fascinating legal squabble way back in 1996 or so when I lived in Philadelphia. This concerns the infamous Holdeen Trusts, and a series of cases and legal disputes centered around same. An article about it in the Philadelphia Inquirer caught my notice because it concerned the efforts of an eccentric millionaire New York lawyer, Jonathan Holdeen, to set up a series of trusts that would one day totally wipe out taxes, at least in Pennsylvania (see also The Holdeen Funds, by Rajan Mylavaganam, below).

Holdeen set up a labyrinth of trusts in Pennsylvania in the 1940s and 1950s, lasting for hundreds of years, with the accumulated trillions of dollars to be eventually used to endow and completely fund the operation of the government of Pennsylvania. He chose Pennsylvania, believing that that state’s laws were most favorable to the validity of such trusts. Holdeen “modeled his plan somewhat after that of the thrifty Benjamin Franklin who limited himself ot two hundred years (1790-1990).” (Holden v. Ratterree, 270 F.2d 701 (2d Cir. 1959); see also Holdeen v. Ratterree, 190 F.Supp 752 (N.D. N.Y. 1960); In re Trusts of Holdeen, 486 Pa. 1, 403 A.2d 978 (1979).)

Unfortunately, in 1977, a “judge ruled invalid a plan Holdeen had dreamed up to make Pennsylvania’s the first tax-free government in the history of the world.” Over the years, Holdeen deposited $2.8 million in several charitable trusts for the benefit of Pennsylvania. “His plan was to let the trusts grow, and to keep plowing the investment income back into them, for 500 to 1,000 years. Since charitable trusts are tax-exempt, the pool of money would become immense.”

By Holdeen’s calculations, the trusts would contain quadrillions or quintillions of dollars after a few centuries – more than enough to pay all the expenses of Pennsylvania government. All state taxes could then be abolished, and Pennsylvania would be a tax-free model for the world.

The Internal Revenue Service pounced on the plan right away. The tax agency saw it as an elaborate scheme by Holdeen to avoid taxes and to benefit his family.

[…] From the 1940s to the 1970s, Holdeen and his heirs battled with the IRS over the validity of the charitable trusts. In the end, the IRS lost. The U.S. Tax Court ruled in 1975 that the trusts were legitimate.

But a separate legal fight had developed in 1971 in Orphans Court, which has jurisdiction over trusts and estates in Pennsylvania.

To try to make his plan conform with legal requirements, Holdeen had named the Unitarian Universalist Church as a beneficiary of charitable trusts, with the understanding that the church would get a tiny portion of the yearly trust income.

While Holdeen was alive, church officials consented to the arrangement. After his death, the church filed suit in Orphans Court seeking all the income. Its lawyers contended that piling up money for 500 or 1,000 years was unreasonable and potentially dangerous.

Eventually, the church argued, the Holdeen trusts would soak up all the world’s money, and Jonathan Holdeen’s descendants, who were to remain in charge of the trusts, would have unimaginable power.

In 1977, [Judge] Pawelec ruled in favor of the church, concluding that Holdeen’s scheme was ‘visionary, unreasonable and socially and economically unsound.’

From then on, income from the trusts, which had grown to more than $20 million, was paid to the Unitarian Church at about $1 million a year.

My idea is that a similar idea could be used to set up some kind of trust that, in time, could accumulate billions of dollars in assets, that could be used to fund a massive anti-state think tank/activist center. The appropriate state or country to be used as a base would have to be investigated, but it could be seeded with a very small amount of money. Suppose it was seeded with $1000. Then over time, it would grow to some arbitrarily large size. It might take 300 years, but so what?–our activist efforts are aimed at the long term and the future anyway. The trust instrument could specify criteria for when the principal, the trust corpus, could start being used–say, when it reaches $500B (inflation-adjusted).

SEE BELOW ***

❧

From Mises Blog: The Future of Freedom Fund and the “Unimaginable Power” of the Holdeen Trusts “soaking up all the world’s money”.

(archived comments below)

The Future of Freedom Fund and the “Unimaginable Power” of the Holdeen Trusts “soaking up all the world’s money”

I recently stumbled across an old blogpost of mine about a fascinating legal squabble I learned about when I lived in Philadelphia. This concerns the infamous Holdeen Trusts, and a series of cases and legal disputes centered around these trusts. I learned about it in an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer by L. Stuart Ditzen, “Quiet Finish To A No-tax Dream Visionary’s Plan To Wipe Out Pa. Taxes Ends After A 50-year Legal Fight,” (Oct. 9, 1996).1 As Ditzen’s article notes:

A 50-year legal battle set off by a fanatically thrifty millionaire who wanted to do away with taxes in Pennsylvania forever – and make his descendants rich at the same time – has come to an end in Philadelphia Orphans Court.

Sadly, the people of Pennsylvania are still going to have to pay taxes.

The legal case, involving a labyrinth of trusts created in the 1940s and 1950s by an eccentric New York lawyer named Jonathan Holdeen, was settled without a trial last Wednesday in the chambers of Judge Edmund S. Pawelec in City Hall.

What happened here was that an eccentric millionaire and New York lawyer, Jonathan Holdeen, set up a complicated series of trusts that he hoped would one day totally wipe out taxes, at least in Pennsylvania. Holdeen set up the trusts in Pennsylvania in the 1940s and 1950s, which were to last for hundreds of years, with the accumulated trillions of dollars to be eventually used to endow and completely fund the operation of the government of Pennsylvania. He chose Pennsylvania, believing that that state’s laws were most favorable to the validity of such trusts. Holdeen “modeled his plan somewhat after that of the thrifty Benjamin Franklin who limited himself to two hundred years (1790-1990).”2

Unfortunately, in 1977, a “judge ruled invalid a plan Holdeen had dreamed up to make Pennsylvania’s the first tax-free government in the history of the world.” Over the years, Holdeen deposited $2.8 million in several charitable trusts for the benefit of Pennsylvania. “His plan was to let the trusts grow, and to keep plowing the investment income back into them, for 500 to 1,000 years. Since charitable trusts are tax-exempt, the pool of money would become immense.”

By Holdeen’s calculations, the trusts would contain quadrillions or quintillions of dollars after a few centuries – more than enough to pay all the expenses of Pennsylvania government. All state taxes could then be abolished, and Pennsylvania would be a tax-free model for the world.

The Internal Revenue Service pounced on the plan right away. The tax agency saw it as an elaborate scheme by Holdeen to avoid taxes and to benefit his family.

[…] From the 1940s to the 1970s, Holdeen and his heirs battled with the IRS over the validity of the charitable trusts. In the end, the IRS lost. The U.S. Tax Court ruled in 1975 that the trusts were legitimate.

But a separate legal fight had developed in 1971 in Orphans Court, which has jurisdiction over trusts and estates in Pennsylvania.

To try to make his plan conform with legal requirements, Holdeen had named the Unitarian Universalist Church as a beneficiary of charitable trusts, with the understanding that the church would get a tiny portion of the yearly trust income.

While Holdeen was alive, church officials consented to the arrangement. After his death, the church filed suit in Orphans Court seeking all the income. Its lawyers contended that piling up money for 500 or 1,000 years was unreasonable and potentially dangerous.

Eventually, the church argued, the Holdeen trusts would soak up all the world’s money, and Jonathan Holdeen’s descendants, who were to remain in charge of the trusts, would have unimaginable power.

In 1977, [Judge] Pawelec ruled in favor of the church, concluding that Holdeen’s scheme was ‘visionary, unreasonable and socially and economically unsound.’

From then on, income from the trusts, which had grown to more than $20 million, was paid to the Unitarian Church at about $1 million a year.

A fascinating legal squabble. It would probably not be a good idea to fund a state like this, even if it would mean no taxes, since the state would just use this immense wealth to wage war and wield power over its subjects. But a similar idea could be used to set up some kind of trust that could in time accumulate billions of dollars, to endow a massive anti-state think tank/activist center–or a group like the Mises Institute. Imagine finding a jurisdiction where such trusts are permitted, setting it up, and in 200-300 years, the Mises Institute has a $500 billion endowment. Ah, well, one can dream.

- 1.See also The Holdeen Funds, by Rajan Mylavaganam.

- 2.Holdeen v. Ratterree, 190 F.Supp 752 (N.D. N.Y. 1960); In re Trusts of Holdeen, 486 Pa. 1, 403 A.2d 978 (1979).

December 15, 2004 at 5:39 pm

-

An interesting idea. The Church’s arguments that the fund would eventually gobble up all of the money in the world are absurd hogwash, of course. In the extremely unlikely event that someone managed to acquire all of the money in the world (lets say gold), some other medium would be chosen by the free market to serve as money.

December 15, 2004 at 5:46 pm

-

I’d also like to comment on the nerve of the church to accuse the man’s daughter of malinvestment, when she’d consistently outperformed the S&P 500. This is compounded by the fact that this Church is the beneficiary of the gift, and should be grateful for what it gets. Talk about ingratitude. Holdeen should also be commended for his vision and far-sightedness.

Civilization is built upon the strength of those with extremely low-time preferences, like Mr. Holdeen:

“He broke up produce crates and burned them for fuel in the wood stove of his frame house in

Pine Plains, N.Y. He cooked in tin cans. And when the elbows of a sweater became worn, he cut

off the sleeves and wore what was left as a vest.” December 15, 2004 at 9:32 pm

-

Never put money into any scheme involving the word “faith” or the word “trust.”

December 15, 2004 at 10:01 pm

-

“By Holdeen’s calculations, the trusts would contain quadrillions or quintillions of dollars after a few centuries – more than enough to pay all the expenses of Pennsylvania government. All state taxes could then be abolished, and Pennsylvania would be a tax-free model for the world.”

Even if he gave the state of Pennsylvania a few quadrillion dollars, the state wouldn’t necessarily eliminate taxation. Look at what happened to the state budget of California during the tech boom. Governments can always find a way to spend windfall profits. The real problem with the plan is that it assumes there is a certain level of financing that a state will consider sufficient.

December 16, 2004 at 1:18 pm

-

“The real problem with the plan is that it assumes there is a certain level of financing that a state will consider sufficient”.

“Never put money into any scheme involving the word ‘faith’ or the word ‘trust.’”.

Sad but true. It was all too predictable how this would turn out. And yet, there are some things that, while predictable, are outrageously unbelievable:

“In 1977, [Judge] Pawelec ruled in favor of the church, concluding that Holdeen’s scheme was ‘visionary, unreasonable and socially and economically unsound.’”.

October 23, 2006 at 8:05 am

-

Unfortunately Holdeen’s vision wasn’t clear enough to see that naming the church & the government, two totally corrupt institutions, as beneficiaries would never yield the desired results.

❧

Future of Freedom Fund

LewRockwell.com, September 5, 2003

Stephan Kinsella

I recalled recently an utterly fascinating legal squabble I read about when I lived in Philadelphia. This concerns the infamous Holdeen Trusts (link 2), and a series of cases and legal disputes centered around same. An article about it in the Philadelphia Inquirer caught my notice because it concerned the efforts of an eccentric millionaire New York lawyer, Jonathan Holdeen, to set up a series of trusts that would one day totally wipe out taxes, at least in Pennsylvania.

Holdeen set up a labyrinth of trusts in Pennsylvania in the 1940s and 1950s, lasting for hundreds of years, with the accumulated trillions of dollars to be eventualy used to endow and completely fund the operation of the government of Pennsylvania. He chose Pennsylvania, believing that that state’s laws were most favorable to the validity of such trusts. Holdeen “modeled his plan somewhat after that of the thrifty Benjamin Franklin who limited himself ot two hundred years (1790-1990).” (Holden v. Ratterree, 270 F.2d 701 (2d Cir. 1959); see also Holdeen v. Ratterree, 190 F.Supp 752 (N.D. N.Y. 1960); In re Trusts of Holdeen, 486 Pa. 1, 403 A.2d 978 (1979).)

Unfortunately, in 1977, a “judge ruled invalid a plan Holdeen had dreamed up to make Pennsylvania’s the first tax-free government in the history of the world.” Over the years, Holdeen deposited $2.8 million in several charitable trusts for the benefit of Pennsylvania. ” His plan was to let the trusts grow, and to keep plowing the investment income back into them, for 500 to 1,000 years. Since charitable trusts are tax-exempt, the pool of money would become immense.”

“By Holdeen’s calculations, the trusts would contain quadrillions or quintillions of dollars after a few centuries – more than enough to pay all the expenses of Pennsylvania government. All state taxes could then be abolished, and Pennsylvania would be a tax-free model for the world.

“The Internal Revenue Service pounced on the plan right away. The tax agency saw it as an elaborate scheme by Holdeen to avoid taxes and to benefit his family.

“[…] From the 1940s to the 1970s, Holdeen and his heirs battled with the IRS over the validity of the charitable trusts. In the end, the IRS lost. The U.S. Tax Court ruled in 1975 that the trusts were legitimate.

“But a separate legal fight had developed in 1971 in Orphans Court, which has jurisdiction over trusts and estates in Pennsylvania.

“To try to make his plan conform with legal requirements, Holdeen had named the Unitarian Universalist Church as a beneficiary of charitable trusts, with the understanding that the church would get a tiny portion of the yearly trust income.

“While Holdeen was alive, church officials consented to the arrangement. After his death, the church filed suit in Orphans Court seeking all the income. Its lawyers contended that piling up money for 500 or 1,000 years was unreasonable and potentially dangerous.

“Eventually, the church argued, the Holdeen trusts would soak up all the world’s money, and Jonathan Holdeen’s descendants, who were to remain in charge of the trusts, would have unimaginable power.

“In 1977, [Judge] Pawelec ruled in favor of the church, concluding that Holdeen’s scheme was ‘visionary, unreasonable and socially and economically unsound.’

“From then on, income from the trusts, which had grown to more than $20 million, was paid to the Unitarian Church at about $1 million a year.”

See also Top 100 Largest Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings by Total Assets.

SEE MISES BLOG VERSION WITH ARCHIVED COMMENTS BELOW

❧

The Holdeen Funds

by Rajan Mylavaganam

(pasted here from the archive version)

In this paper1 I will inquire into the establishment of the Holdeen Funds and the management of these trust funds by the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations (UUA), the nominal beneficiaries so designated by the benefactor, Jonathan Holdeen. The Holdeen Funds have been represented to the Internal Revenue Service and promoted to the public by the UUA as intended for the impoverished people of India. Was this the original intent for the Funds, and have these intentions been respected?

I shall seek to show that there are serious discrepancies between the manner in which the income from the Holdeen Funds are being expended and their ascribed purposes. These manipulations may be serious enough to raise questions about the financial morality of the individuals responsible for administering the Holdeen Funds. Has the Board of Trustees of the UUA contravened the legal limits of the Holdeen Funds in the appropriations for the year 2000? This and other equally contentious questions will be asked throughout this paper and efforts made to answer them. Perhaps it is appropriate to begin by asking, “Who is Jonathan Holdeen?” and “What are the Holdeen Funds?”

I first heard mention of Jonathan Holdeen at Meadville Lombard Theological School, Chicago, Illinois where I had enrolled as a Doctor of Ministry candidate in September 1988. A seminary colleague of mine, on hearing of my interest in Indian Unitarians, contributed that a man named Jonathan Holdeen had left a considerable sum of money for “the poorest of the poor in India.” 2 I thought to myself, “How nice that Mr. Holdeen had left all this money for the poor people of India.” It affirmed my choice to be a Unitarian and I congratulated myself for having made the wise choice of becoming a student at a Unitarian seminary.

I discovered that the UUA is a liberal religious organization that has some 200,000 members and 1003 congregations; and is the result of a merger between the American Unitarian Association and the Universalist Association. While small in numbers the Unitarian Universalists (UU) have had a far greater political representation in proportion to their numbers in the formal politics of State than most denominations. They are noted for taking bold social positions and are usually at the forefront of political, social and religious controversies that come before change and have been so since their inception in 1825. (See Chapter on William Roberts).

I skipped my second year at seminary to find out more about my new religious home by beginning a ministerial internship at the May Memorial Unitarian Society, Syracuse, New York. My training included conducting church services one Sunday a month. On one such Sunday, during the congregation’s response to my sermon on Indian Unitarians,3 I learned that Jonathan Holdeen had been a familiar, if somewhat eccentric, figure in Syracuse. From that time on I have noticed brief mentions of the Holdeen Fund in the UUA’s annual directory. There was, however, very little real information on Jonathan Holdeen or the Holdeen Funds, and not many were willing or able to speak knowledgeably on the subject of these Funds. In fact a recent request for information from International Office at the UUA drew this response from their Director, the Reverend Olivia Holmes, “Holdeen has nothing to do with your subject as far as I can tell.”4 The response seemed unusual given the huge amounts of Holdeen Fund moneys that were being spent by the UUA, and all of it in the name of the impoverished people of India.

It is now no longer difficult to access information on non-profit, charitable organizations that seek public financial contributions.5 In an article posted on the World Wide Web in October 1996 Chuck Shepherd, editor and compiler of the column, “News of the Weird,” wrote,

The Unitarian Universalist Church and heirs of Jonathan Holdeen settled their 20-year-old dispute on the disposition of Holdeen’s estate, which was created in 1945 as a series of trusts that eventually would have amassed so much money they would have allegedly have funded the entire federal government and rendered taxation unnecessary. In fact, the Church which was a nominal beneficiary of the trusts, argued for their abolition in 1977 on the ground that they would soak up so much of the world’s money that the administrators of the trusts would become too powerful.6

Shepherd compiled his column from actual news articles, and readily provided the source of the report upon my request. As it turned out the primary reporter for the stories on Jonathan Holdeen and the trusts he created was L. Stuart Ditzen.7 Ditzen reported on the court hearings between the UUA and Janet Adams Holden, Jonathan Holdeen’s daughter, in the Philadelphia Inquirer.8 These reports, along with United States Tax Court Reports,9 Form 990s filed by the Holdeen Funds10 make up the primary non-UUA sources for this paper. The majority of other sources for this paper come from UUA postings on the World Wide Web.11 The other significant organization whose record was examined for this paper is the Liberal Religious Charitable Society Inc.,12 a non-profit organization that is associated with the UUA.

The biographical material on Jonathan Holdeen presented here is culled from U.S. Tax Court reports.13 (This strange man did not even warrant an obituary in the New York Times).14 The court reporting reveals that Jonathan Holdeen was born Jonathan Holden in Sherburne, Chenango County, New York on 16 September 1881. He attended Colgate University until 1901. Upon graduation he worked in the law office of his father Stephen Holden before being admitted to the New York State bar in 1903. After gaining experience examining land titles at Title Guaranty & Trust Company in New York City he opened his own law office in Pleasantville, New York. He engaged more in business than practiced law, and during his lifetime built up considerable real estate holdings.

In 1932 he established an office in Poughkeepsie, and except for a brief spell of several months in 1940, he resided in Pine Plains until 1961. On the death of his wife, Stella Hamblen, he moved back to his birthplace, Sherburne, New York. From 1964 until 1967 Holdeen was the owner and resident of Onandaga Hotel in Syracuse, Central New York.15

Holdeen married Stella Hamblen in 1910 and by 1957 they had ten children and twenty-five grandchildren.16 In 1931 Jonathan changed his surname from Holden to Holdeen in an apparent attempt to distinguish his family as ” the Northern Westchester branch of the family.”17 The Court records the fact that other members of his family refused to change their names and his wife continues to be referred as Stella Holden in the Court’s reports.18 Jonathan Holdeen died on 14 June 1967 in relative obscurity, without as has already been noted, even getting a mention in the New York Times obituary column. This was incredible given that he invested large sums of money in a practical effort to rid the world of taxation.

Holdeen was motivated in his unusual plans for the governments of the world by Benjamin Franklin. As Holdeen noted in his article, “Should Thrift be Nationalized?”, which was published along with other papers by Oswego Press, Cooperstown, New York.19

One of the first American statesmen performed an act which is suggestive of possibilities. When Benjamin Franklin died, it was found that besides providing for his children, he had made a number of philanthropic bequests out of his modest estate, two of which were unusual. He gave two funds of five thousand dollars each, one for Philadelphia where most of his life was passed and the other for Boston which was his native city. These funds were directed to be invested by being loaned to apprentices, starting in business for themselves, at 5% interest. The income was to be accumulated for one hundred years when the greater part of each fund was to be expended in providing some building or public work for the betterment of each city. As might be expected from the character of the investments, there were some losses. Nevertheless at the end of the century, Franklin’s Philadelphia fund is said to have increased from $5,000 to $450,000. There was a delay of some years while the citizens debated what to build with the fund. Meanwhile it increased to something like $650,000. The Boston fund has a similar history.20

An interesting afterword to Franklin’s wish for posterity was that the Massachusetts Legislature in 1958 tried to expropriate Franklin’s Boston Fund,21 and Holdeen “printed and sent to the members of the Legislature a protest against such action”.22

Holdeen opined that society in general would not address such questions as frugality and thrift and decided that it was possible that an individual had “it in his power to set in train, a process which will contribute more forcefully to that end than exhortion”.23 He set out to be that individual by entering into “some 186 agreements with his adult daughters or friends.”24 He maintained the principle of providing for his family first, including his children, nephews, nieces and grandchildren, with a part going to charity. This would later become one of the contentions raised by lawyers for the IRS, and the UUA’s lawyers, in efforts to breakup the Holdeen trusts. The experts testifying for the UUA argued that the trusts created by Holdeen’s scheme were a plot to empower and enrich his family out of all proportion to what can be considered appropriate and beneficial to the issue of a tax free environment in Pennsylvania.25 Holdeen had named tax exempt organizations including the American Unitarian Association as the nominal beneficiaries,26 anticipating such challenges from the IRS who saw his schemes as an elaborate effort to avoid taxation. Holdeen could not have anticipated the AUA’s merger with the Universalists or that the succeeding organization, the UUA, would not live up to his expectations of financial morality. The leaders of the UUA whom Holdeen chose over his family or the State would eventually betray his faith in them, as I shall demonstrate through this paper.

Holdeen’s trusts were simple in their concept and in the math. In designing his scheme Holdeen set aside a total of $2.8 million in varying sums and at different times, stipulating that the income from the investments be allowed to accumulate. After a period of five hundred years, and in some instances a thousand years, the principal and accumulated income was to be paid to the State of Pennsylvania.27 Pennsylvania could than use the income to pay for the necessary expenses of government. At least that was Holdeen’s plan, if it had survived. But we will never know, thanks to the UUA.

As early as 1913 Holdeen willed that a portion of his estate be used to promote his ideas, encouraging the nations of the world to accumulate enough income to meet expenses of government without a requirement for taxation.28 Was he already moving past his mentor Benjamin Franklin who is thought to have coined the saying, ‘Only death and taxes are inevitable’? Holdeen, perhaps hearing an echo of Benjamin Franklin’s claim, may have decided to prove his hero wrong on at least one of the two counts. He wanted to make Pennsylvania the first state in the Union that would not have to depend on taxation for its operations even if Pennsylvanians would have to wait 500 to 1000 years to realize their dream.29 Questions were raised about his efforts. Was Holdeen being prophetic and seeking to challenge conventional wisdom, or was he merely participating in the tried and true American pastime of avoiding personal taxation as charged by the IRS? Or was he seeking to assure his family unimaginable power over the people of the world, as charged by the UUA? I have not had the opportunity to peruse Holdeen’s writings30 and cannot provide conclusive answers to these questions at this time. What I can do is assure the reader that Holdeen was serious about his commitment. In 1932 when the market value of the entire real and personal property in the world was less than one trillion dollars,31 Holdeen provided specific formulas for the implementation of his plans to abolish taxation.

Holdeen was aware that his was an experimental idea and would be subject to challenge. He conceded that “the history of the past, with its records of invasions and revolutions proves that … an accumulated endowment … created two thousand years ago …would not (have) survive (d)”32 to 1912. Yet Holdeen was persuaded that advances that had been made in successive civilizations made it possible for futuristic thinking on his scale. He was sufficiently convinced that the time for his plan to eliminate waste and provide future leaders with resources to do the work of government was at hand. Holdeen believed that the inhabitants of the earth had reached “a stage of civilization when vested property rights will be unmolested even in case of conquest, unless they unusually conflict with the common welfare”.33 Holdeen cited the example of William of Wickham and his endowment for Winchester College, England in 1393,34 which had withstood the test of time, as a model for his faith in his system. Holdeen’s effort to follow his vision for the fiscal independence of the governments of the world was, however, challenged from two quarters, the IRS and the UUA. His efforts to defend the trusts occupied him, and after he died in 1967, his daughter, Janet Holden Adams, for the better part of fifty years.35

To accomplish his goal Holdeen put money over the years into a number of trusts and made the American Unitarian Association and other non-profit organizations the nominal beneficiaries, with control in the hands of his descendants and the final beneficiary the State of Pennsylvania.36 It was part of the plan that the AUA use their portion of income to assist the natives of India, their descendants and Asians in general.37 As soon as Holdeen died challenges were made to the trusts. No one seemed to like the scheme, except perhaps the taxpayers of Pennsylvania:

The government of Pennsylvania didn’t like it; the Internal Revenue Service absolutely loathed it. And the national Unitarian Universalist Church of Boston [sic], which played a key role in Holdeen’s plan, disapproved one part of it – the part that set aside earnings of the trust for Pennsylvania. The church wanted the money, instead, but did not declare that until after Holdeen died in 1967.38

The first challenge to his unorthodox vision came from the Internal Revenue Service which, not unexpectedly “waged a 30-year legal battle to prove that the trusts were part of an elaborate scheme by Holden [sic] to avoid taxes and benefit his family.”39 Jonathan Holdeen, succeeded by his daughter, Janet Holden Adams, successfully staved off the challenge of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue. In 1975 the judge held that the trusts initiated in 1945 were legal and “had no taxable incomes in the years involved.”40

This was not the end of Holdeen’s problems. The UUA now took their turn at breaking the trusts.

The Court reports indicate that Holdeen, based on correspondence he had with Percy W. Gardner, had on 8 November 1944 invited the AUA to participate in his financial plan. In his letter he had specifically offered the AUA the opportunity to make any revisions.41 At that time the American Unitarian Association agreed with and gave legitimacy to Holdeen’s plan in return for a small portion of the income from his scheme. The participating of a non-profit charitable organization was necessary for Holdeen’s scheme to conform to Pennsylvania’s law since Pennsylvania was one of the few States to permit this type of idea. More importantly, the AUA had no objections to any of this in 1944. The UUA, successor organization to the AUA, did not agree and upon Holdeen’s death in 1967 began legal proceedings to get all the money. Ditzen headlined one of his articles:

“DREAM TO END TAXES NOW A NIGHTMARE (-) LAWYER WANTED TO USE INCOME FROM TRUST FUND TO RUN PENNSYLVANIA; CHURCH FIGHTS FOR MONEY.”42

Nor was the State prepared for Holdeen’s plan. As Ditzen observed the “Pennsylvania attorney general’s office stood with the church.”43

The UUA argued through its lawyers that “piling up money for 500 and 1,000 years was an unreasonable and potentially dangerous”44 activity for a charitable trust. Under the sub-heading, “Doomsday Predictions” the newspaper commented: “During the drawn-out proceedings in Orphans Courts in the 1970’s church lawyers presented experts who made hand-wringing predictions about the fast-growing Holdeen trusts.”45 Holdeen’s plan was once again under attack – this time from the very Church that had agreed to legitimize it. The UUA’s lawyers presented experts to persuade Judge Edmund S. Pawlec that the trusts if allowed to “continue for hundreds of years … would balloon so large that they would sponge up all the money in the world.”46 One economist declared “that the trusts would grow so big that ‘they [Holdeen’s descendents] would absolutely own the world’.”47 Another direly predicted, “Any time you wanted to make a telephone call or take a trip … you would be paying money to the Holdeens. … And everyone in the world would work for the Holdeens’.”48 The Holdeen family countered by presenting Gardner Ackley, former chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers, as their witness: “Ackley scoffed at the Church’s experts. He testified that Holdeen’s notion was a good idea.”49 Ackley’s testimony was not sufficient to sway the judge’s opinion. Judge Pawlec found Holdeen’s plan to be “contrary to public policy”.50 In his 1977 opinion Judge Pawlec wrote:

The expressed purpose [of the plan] is so visionary, unreasonable and socially and economically unsound that we must conclude the entire plan is charitably purposeless, contrary to public policy and hence void.51

Two years later the Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld the Judge’s opinion and the Holdeen trusts were broken.52

The portions of incomes from the trusts due to accumulate toward Holdeen’s grand objective of a tax free Pennsylvania was now to be turned over to the UUA. The UUA, which had been invited to participate in Holdeen’s long range vision to alleviate the burden of taxation in return for one five-hundredth of the income was now to receive “all the income of the trusts, past and future.”53 Janet Holden Adams was still the trustee and was not ready to give up the ghost. It must have been difficult for a daughter to see her father’s dream end in this way. She responded by holding back the trust income to the UUA.54 “And she started giving money to other charities. ‘Once they broke the trust, I figured, heck’, she says by way of explanation. ‘I wouldn’t give them a nickel if I had a choice’.”55

The UUA proceeded to bring lawsuits against Janet Holden Adams that lasted for 20 years. The legal battles could have ended here but unfortunately for Janet Holden Adams, who was now 82, the UUA began accusing her of “mismanagement, self-dealing and fraud … [and] demand[ed] $12 million in damages.”56 Adams’ lawyers countered by saying that the trusts under Adams’ care had done very well. Her investment strategy had outperformed the stock averages for Dow Jones and Standard & Poor. “And they earned huge dollops of income – money that was intended to endow Pennsylvania but that has been paid, instead under court order to the church.”57

The UUA had been unremitting in its efforts to challenge Janet Holden Adam’s management of the trusts. Their lawyers, no less aggressive, had charged $932,000 by March 1994, to be paid out of the Pennsylvania trusts.58 The Church apparently had been transformed during this process and began behaving as “the IRS had done in the 1940’s and 50’s and 60’s, [sending] accountants to scrutinize the books and records”.59 Yet by 1986 the UUA had apparently backed off from their difficult position, with lawyers for the Church telling Judge Pawlec that they were satisfied with the way the trustees had managed the investments.60

Three years later, however, the UUA sent its lawyers out again demanding that the trustees be changed, and Adams resigned in 1989. This did not stop the lawyers for the UUA from summoning her three times to Philadelphia from her home in Pine Plains, New York “for a total of 13 days of depositions in which they have grilled her on the details of 45 years of investments.”61 Even the judge was beginning to express concerns about the legal battles in his courtroom. In a conference in 1992, Judge Pawlec called for a limit in some fashion to the burgeoning legal fees, adding, “We have to use some kind of common sense in trying to bring this to a resolution.”62 The dispute was finally settled in 1996 without a trial. The UUA became the sole and undisputed distributors of the income from the trust that Jonathan Holdeen had established. By 1996 the UUA had “received $21.9 million [and] the income continues to flow at the rate of $1 million a year”.63 The UUA was now in charge, receiving trust income from a bank in Philadelphia.

Listed below are excerpts from six Form 990’s filed with the Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, by First Union National Bank (as trustees) for the Holdeen Funds and the income received by the UUA for 1999:

Fund Number UUA’s Income

Holdeen Fund 45-10 $258,423

Holdeen Fund 50-10 $75,128

Holdeen Fund 46-10 $25,973

Holdeen Fund 47-10 $933,130

Holdeen Fund 54-120 $61,963

Holdeen Fund 55-10 $339,00664

Total $1,793,623

In each of these filings with the IRS the response to the question, ‘Purpose of grant or contribution’ (Part XV 3A) is,

For endowment or other use in aid of maternity, child welfare and educational and migration expenses of natives of India [or Asia] and their descendants.65

The IRS documents provide final confirmation that the Holdeen Funds are inextricably linked to the people of India, their descendants and Asians in general.66 Holdeen India Program (HIP) which operates out of the Washington, DC office is perhaps the least arbitrary of the UUA’s efforts to fulfil its trusteeship. HIP claims, and I have no reason to doubt this claim, to be assisting the most impoverished groups in India in a direct way in areas of greatest need. HIP works through registered voluntary Indian organizations sympathetic to HIP’s aims.67 Katherine Sreedhar, Director of HIP, writes, “We are in India to increase people’s power, to help them improve their livelihood and their quality of life.”68 Some of the groups receiving assistance from HIP:

- Self-Employed Women’s Association, a self-governing union founded in 1971 with a current membership of over 30,000. SEWA runs a cooperative bank, a self-funded social security plan, and various income-producing ventures, and has advocated for policy changes for unorganized sectors of society.

- Deccan Development Society promotes village self-help through cooperative women’s groups called sangams. Now there are more than 30 sangams which have made over 200,000 rupees available for short-term loans to help support change in farming communities.

- Annapurna Mahila Mandal is building a women’s center, and helping secure bank credit for the thousands of women who support themselves by preparing meals for unattached men who left their villages and families to seek work.

- Vidhayak Sansad attacks the problem of bonded labor, when a debtor is forced to pay off a landlord’s loan by working exclusively for the landlords. Such people have no right to bargain, strike, or leave; though bonded labor was technically outlawed in 1976, more than 2 million people are still in its thrall. Vidhayak Sansad trains people to seek their freedom, teaches them how to avoid debt, and has developed employment projects for newly freed laborers, displaced tribals, and other ‘untouchables.’

- Mahiti helped villagers in a perennially drought-stricken area design and build an innovative rain collection project, so that people and cattle can survive and thrive in areas where disease and fighting over life-saving water was the previous order of the day.